In earlier articles, we highlighted how Sweden, Finland, and the United Kingdom are all hitting the brakes on medical transitioning for minors. More countries are following their lead.

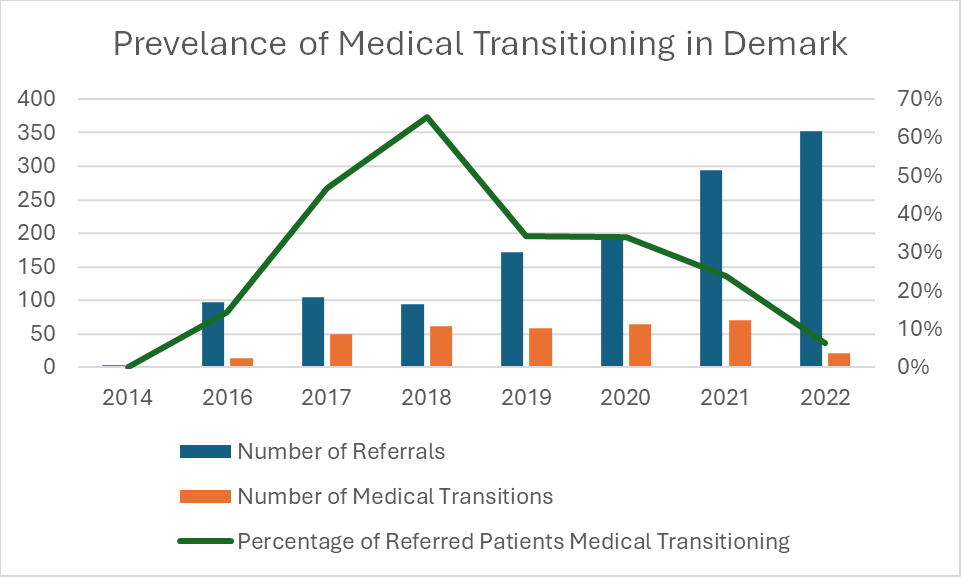

Take Denmark. In 2018, 65% of youth seen by Denmark’s centralized gender service medically transitioned.1 Despite more warning signs popping up and new clinical guidelines being issued in other European countries – particularly in Denmark’s neighbours, Sweden and Finland – Denmark hasn’t officially changed its policies on medical transitioning. Yet, in 2022, only 6% of Danish youth referred to the gender service went on to medically transition, reflecting a new hesitancy among gender specialists in Denmark to refer children and adolescents for a medical transition. That decrease from 65% to 6% shows there is a quiet revolution against medically transitioning minors happening in Denmark.

Denmark saw a steady rise in the number of youth coming to gender clinics with gender dysphoria, from 4 in 2014 to 352 in 2022. The percentage of these youth referred for medical transitioning has steadily fallen since 2018, though the absolute number of medical transitions only really fell significantly between 2021 (70) and 2022 (22). To take a page out of Shakespeare, something was rotten in the state of Denmark, but the Danes picked up the scent and have begun cleaning things up.

The medical establishment in Germany is calling on the government to replace its politically motivated approach to treating gender dysphoria with an evidence-based approach.

Or take Germany. Earlier this month, the 128th German Medical Assembly met. This association, self-described as “the central organisation in the system of medical self-administration in Germany,” is made up of delegates from the 17 state/provincial physician bodies. At their recent meeting, they passed a resolution calling on the German government to strictly limit medical transitioning for minors and for medical transitioning only to be permitted in controlled scientific studies.

The resolution says that “current medical evidence clearly and unambiguously states that puberty-blocking drugs (PB), opposite-sex hormone treatments (so-called cross-sex hormone administration [CSH]) and gender reassignment surgery (e.g. a mastectomy) do not improve GI/GD [gender incongruence/gender dysphoria] symptoms or mental health in minors with GI/GD. These are irreversible interventions in the human body in physiologically primarily healthy minors, who cannot give informed consent in the absence of evidence for such measures.”

Regrettably, the German government recently updated its official guidance in a manner that supports medical transitioning for minors. But the medical establishment in Germany is calling on the government to replace its politically motivated approach to treating gender dysphoria with an evidence-based approach.

Medical transitioning may be “one of the greatest ethical scandals in the history of medicine.”

Report from French Senators

Or take France. A group of French Senators initiated a report on medical transitioning for minors. The report, published earlier this year, claimed that the prevalence of medical transitioning may be “one of the greatest ethical scandals in the history of medicine.” Although the legislation hasn’t formally been introduced yet, several senators are working on a bill to prohibit medical transitioning for minors entirely in the country that they hope to introduce this summer.

And this is after the National Academy of Medicine in France released a statement urging medical practitioners to use the “greatest caution” when prescribing puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones, given “the side-effects such as the impact on growth, bone weakening, risk of sterility, emotional and intellectual consequences and, for girls, menopause-like symptoms.”

Actually, take psychiatric bodies across Europe. The European Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (ESCAP) is an umbrella organization with societies in 36 member countries across Europe that helps its member societies discuss academic evidence in their fields, provide clinical guidance, and develop national health policies. At it’s recent meeting, it restated that an ethical pillar of medicine is to do no harm, a commitment featured in the Hippocratic Oath.

Conversely, the goal of medical interventions is beneficence, to do good. Therefore, any medical intervention must be based on sound science supporting its efficacy to do good and not to do harm, to restore or preserve mental and physical health rather than impairing health. Given the lack of evidence supporting medical transitioning, ESCAP calls on health care providers “not to promote experimental and unnecessarily invasive treatments with unproven psycho-social effects and, therefore, to adhere to the ‘primum non nocere’ (first, do no harm) principle.”

As we can see from all of these examples, there is a growing movement in more and more countries to stop medical transitioning for minors.

Will Canada finally examine the evidence and follow suit?